I Was Radicalized by Dirty Dancing

When I was in elementary school, I knew a girl named Addy. She was a couple years older than me and lived in a different town, so she knew about stuff I didn’t know about—a quality I still appreciate in friendships. Addy’s parents were friends with my parents, so during the summer, she would sometimes get to stay at my house for weeks at a time. During one of these trips, she brought a VHS tape of a movie for us to watch together. That movie was Dirty Dancing.

I had never heard of Dirty Dancing, but my mom had. Because of whatever she had heard about it (up to and including its salacious title), she insisted on watching it with us. I found this somewhat embarrassing, but in retrospect, I think that perhaps even more than chaperoning us, my mom was interested in experiencing the movie for herself. (Spoilers follow.)

On the surface, Dirty Dancing is a coming-of-age story about a teenage girl, based on screenwriter Eleanor Bergstein’s memories of summering with her family in the Catskills in the 1960s. Its protagonist is Jennifer Grey as ‘Baby’ Houseman (whom we later learn is actually named Frances, after Frances Perkins, the first woman to serve in a US presidential cabinet). Like her namesake, Baby has lofty goals: as her father, Dr. Jake Houseman proudly declares, she’s “starting Mount Holyoke in the fall,” and after that, she plans to join the Peace Corps.

As the Houseman family settles into their summer home at Kellerman’s resort, Baby notices that the resort staff comprises two distinct social classes who are treated very differently by the proprietor Max. At the top are the waiters, like the one introduced as Yale medical student Robbie Gould, who come from respectable families and are actively encouraged to socialize with the guests and even romance their teenage daughters. On the other end of the socioeconomic spectrum are the dancers—struggling artists from working class backgrounds who are hired to entertain the guests and give them dance lessons, but will lose their jobs if they cross any lines. As his name suggests, the king of the dancers is Johnny Castle, played by an astonishingly hot Patrick Swayze in all his pre-Road House glory.

Both Max and Baby’s father want to pair Baby off with Max’s nephew, Neil, who is studying hotel management at Cornell. But Baby is fascinated by Johnny, and this fascination leads her to follow Johnny’s cousin up to the shack where the dancers throw their after-hours parties—raucous, racially integrated soirées where cutting edge dance moves percolate in a cauldron of magnificent dry-humping.

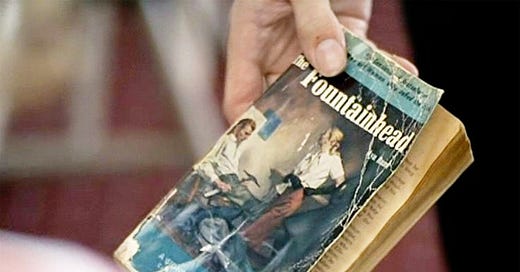

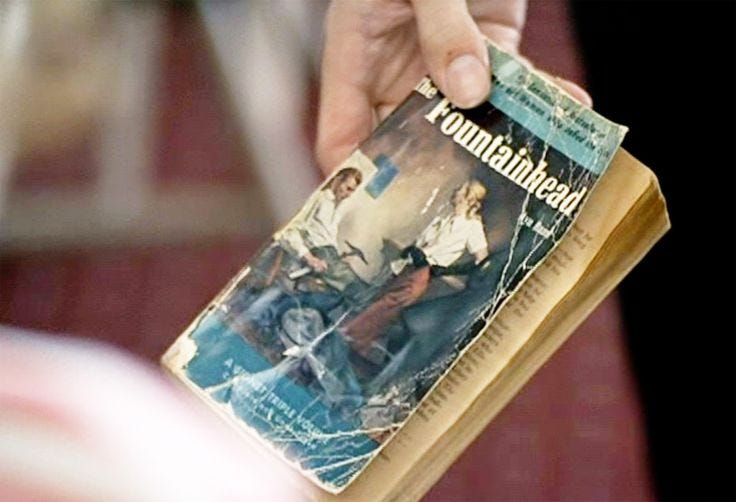

Baby learns that Johnny’s virtuosic dance partner Penny is pregnant, and will lose her job if she doesn’t have an abortion, which she hopes to obtain from an itinerant provider who only takes cash. When she hears that the father is Robbie the waiter, she is optimistic—surely he can afford to give Penny the funds she needs. But when Baby confronts Robbie about Penny’s pregnancy, he rebuffs her, saying “Some people count, some people don’t.” Then he tries to loan Baby his dogeared copy of Ayn Rand’s The Fountainhead (but he needs it back, because he has “notes in the margins.”)

Determined to help, Baby instead procures the money from her father (Jerry Orbach in his greatest role) and agrees to fill in for Penny as Johnny’s dance partner at another hotel, leading to one of the most delightful training montages in Hollywood history. When Baby and Johnny return to Kellerman’s they find Penny doubled over in pain from her botched back-alley abortion, and Baby has to ask for her father’s help again—this time to provide life-saving medical care.

I had never heard of abortion until the first time I watched Dirty Dancing, so some of the plot points went over my head. Later that night, I asked my mom what an abortion was, and she told me. She also explained, in very broad terms, what Roe v. Wade was, and why Penny’s only option for obtaining an abortion was from a sketchy doctor with “a dirty knife and a folding table.” Then I asked my mom if she knew anyone who had had an abortion and she told me that my grandmother’s cousin—an elderly woman who was highly respected in our tiny community—had had an abortion when she was a teenager, back when that sort of thing was seldom done and even more seldom discussed. Because of her abortion, this relative had been able to finish high school and become an adult before starting a family. This conversation was eye-opening, because it took abortion out of the theoretical realm and contextualized it as something that actual people do for real-world reasons.

As it turns out, this kind of conversation was exactly what Bergstein had in mind when she wrote the film. In a 2017 interview with Vice, she explains:

When I made the movie in 1987, about 1963, I put in the illegal abortion and everyone said, "Why? There was Roe vs. Wade—what are you doing this for?" I said, "Well, I don't know that we will always have Roe vs. Wade," and I got a lot of pushback on that. Worse than that, there were also very young women then who didn't remember a time before Roe vs. Wade, so for them I was like Susan B. Anthony, saying, "Oh, just remember, remember, remember."

The decision to include the illegal abortion in Dirty Dancing received significant resistance from the studio. Multiple attempts were made to cut it, but ultimately Bergstein was able to defend it because she had intentionally made it such an integral plot point:

What I always say to people—since people are always complaining that they put serious moral themes in their movies that get taken out—is that if you're putting in a political theme, you really better have it written into the story, because otherwise the day will come when they'll tell you to take it out. And if they can, it will go out. If it's in the corner of the frame, it will always go out.

Eleanor Bergstein wasn’t about to let anybody put abortion rights in the corner. On the contrary, Dirty Dancing’s abortion subplot is inextricably intertwined with its class analysis; a social hierarchy dominated by those who believe that “Some people count, some people don’t.”

Simply put, Penny needs an abortion because she can’t afford to lose work. If the entertainment staff at Kellerman’s had access to things like subsidized contraception, healthcare coverage, or paid parental leave, Dirty Dancing might have been a very different movie. But as it stands, it’s a film that demonstrates the stark contrast between elite apathy and working-class solidarity. Johnny Castle isn’t just hot because of his dancer’s abs and his perfectly coiffed mullet. He is also hot because he is willing to do whatever it takes to help his dance partner in her time of need.

An idealist who believes she wants to do good in the world, Baby sees in Johnny the kind of altruism she wants to develop in herself. In this way, the dancing in Dirty Dancing can be read as allegorical, in that it inscribes a matrix of mutual aid and care. A dance floor is not a battleground. The movements that take place here are coordinated expressions of collective embodiment. Dancers respect each others’ “dance space” and constantly rely on each others’ strength. In the film’s climactic lift scene, Baby learns to defy gravity through trust. Perhaps this is why Ayn Rand thought that most forms of dance did not even qualify as art. Dance is a deeply cooperative enterprise—of course its social, relational aesthetic does not register as valid to the individualism-obsessed ideologue.

Baby began her summer with a strong sense of morality but little experience with the messy work of putting it into practice. The life lessons she took from her encounter with the dancers were about how to be a human being in community with other human beings—a concept that still feels as radical now as it did that summer afternoon watching my friend Addy’s VHS tape. This is why Dirty Dancing stands the test of time as one of the great leftist films.